Apple Intelligence and the Class Fantasy of Seamless AI

by Javier Zulauf

At its Worldwide Developers Conference (WWDC) in June 2024, Apple introduced a suite of generative artificial intelligence (AI) features under the branding “Apple Intelligence”—implemented in Apple’s proprietary voice assistant, Siri. Touted as the company’s most ambitious foray into AI, Apple framed the launch as not just a technological leap but also a moral and aesthetic reimagining of what AI should feel like: private, personalized, invisible, and seamlessly integrated into users’ lives. Craig Federighi, Apple’s senior vice president of software engineering, introduced the system with the tagline “AI for the rest of us” [1]—a phrase that implies inclusivity yet immediately invites scrutiny. Who exactly is the rest of us? What class assumptions are buried in that rhetorical flourish?

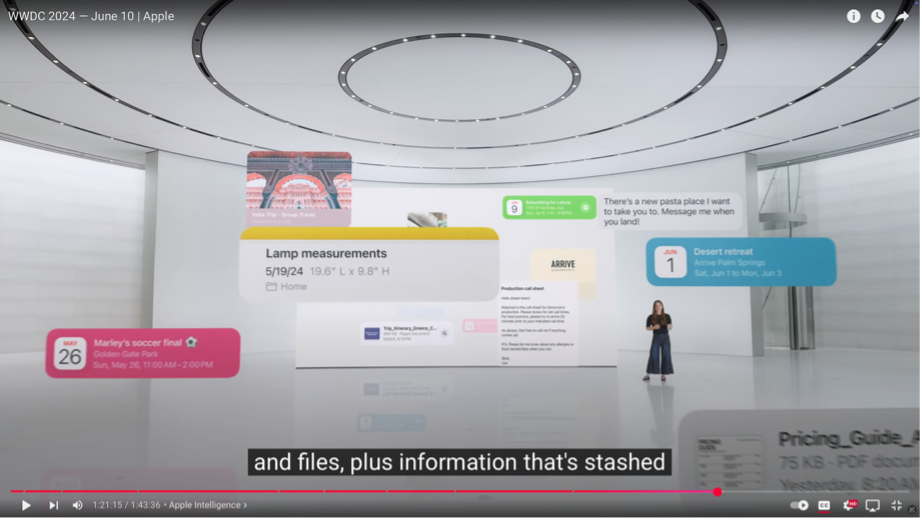

Despite its democratic ring, Apple Intelligence—framed as a personal assistant via its “deep integration” [1] into Siri—is not built for the working class, nor is it designed to address the material conditions of digital inequality. It requires access to the latest iPhones or Macs—devices priced firmly in the realm of upper-middle-class consumption—and is showcased through use-cases that align overwhelmingly with white-collar labor: scheduling meetings, managing emails, summarizing PDFs, and crafting ‘professional’ messages (see figure 1). This techno-utopian narrative of frictionless assistance conceals the very real class barriers that gatekeep access to such technology. Apple presents AI as a universal tool, but the presentation itself—and the ideology underpinning it—is anything but universal.

The term personal assistant carries a deeply classed history. Traditionally, it evokes the figure of a subordinate worker—often feminized or racialized—who performs administrative, emotional, or logistical labor for someone in a position of social or economic power. Presumably, that is why Siri has a female voice by default. In elite corporate and domestic settings, personal assistants function as human buffers between their employer and the messiness of everyday life. Apple has been digitizing and sanitizing this relation through Siri since 2011: It promises the experience of having a subordinate without the ethical, financial, or emotional complications of hiring an actual person. Siri works as a neutral service, unmarked by class—but only for those who can afford to access it.

Apple Intelligence continues to expand this fantasy of classless convenience. By presenting AI as a clean, seamless, and personalized form of labor, Apple erases the economic and social dynamics that enable both its production and use. The rhetoric of “AI for the rest of us” obscures the fact that Apple’s users are already positioned as a socioeconomically privileged class. In staging AI as a natural extension of the Apple lifestyle—minimal, curated, and friction-free—Apple Intelligence repackages class privilege as technological inevitability.

Seamlessness, Surfaces, and the Aesthetic Obfuscation of Labor

Apple’s narrative around Apple Intelligence is grounded in aesthetic seduction: simplicity, intuitiveness, and above all, seamlessness. Federighi emphasizes that AI is now “deeply integrated” into the system—language that suggests not just technical optimization, but a design ideology in which the labor of artificial intelligence disappears behind the operating system’s polished surface. This rhetoric aligns with Fredric Jameson’s diagnosis of late capitalism, where culture “flattens” into surfaces, and depth—whether social, historical, or material—is evacuated in favor of smoothness and immediacy [2]. What matters is not what Siri does, but how effortless it feels while doing it thanks to Apple Intelligence.

In this framework, the user’s alienation is not from their labor (as in classic Marxist terms), but from the mechanisms of the devices they use. Apple actively promotes this disconnection: The more powerful the AI becomes, the less the user is meant to understand—or even notice—it. ‘You won’t have to think about it. It just works.’ This is the idea of intelligence without complexity, functionality without friction, labor without laborers.

This reveals a deeper postmodern contradiction. While Apple Intelligence performs digital labor on behalf of the user, the boundary between the user’s work and the AI’s work collapses. The user becomes the manager of their assistant, but also the product—their data, habits, and preferences continuously extracted and redeployed by the platform. The user is alienated not only from how the system works, but from the value they themselves generate.

This conflation is intensified by the design shift between WWDC24 and WWDC25. In 2024, AI was still tethered to Siri. By 2025, Siri is nearly absent—mentioned only twice, as noted in Marques Brownlee’s reflection on WWDC25 [3]—suggesting a move toward invisible integration. [4] Apple Intelligence is no longer a thing the user interacts with. It is an environment, ubiquitously powerful. This correlates with Apple’s new “Liquid Glass” design language, emphasizing transparency, fluidity, and surface beauty. The irony is that this transparency is politically and economically opaque. [5]

Apple offers a postmodern fantasy of work without labor, assistance without class. The AI assistant becomes a simulation of help—its labor aestheticized, its mechanisms hidden, its political economy erased. The user feels served, but by no one. Behind every seamless prompt is a cloud server, a data broker, a poorly paid content moderator. Intelligence becomes ambient, but it is still extractive.

Class as Omission: The Fantasy of Frictionless Help

Apple’s pivot from “Siri” to “Apple Intelligence” is more than a rebrand—it’s a political shift. Once a quirky, feminized voice assistant, Siri was the friendly face of assistance. In WWDC24 and more so in WWDC25, Siri nearly disappears. In her place, Apple Intelligence emancipates not as a character but as a condition: ambient, integrated, invisible yet ubiquitous. Intelligence no longer needs to be seen but it must be everywhere.

This evolution echoes Lauren Berlant’s concept of cruel optimism: the attachment to fantasies of “the good life,” even when they undermine well-being.

“A relation of cruel optimism exists when something you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing. It might involve food, or a kind of love; it might be a fantasy of the good life, or a political project. […] These kinds of optimistic relation are not inherently cruel. They become cruel only when the object that draws your attachment actively impedes the aim that brought you to it initially.” [6]

Apple sells the dream of hyper-competent self-management. But the costs—energy use, data extraction, exploitative digital labor, let alone the devastating environmental impact of the excessive water consumption—are made invisible. As systems integrate, infrastructure vanishes. The assistant dissolves into your phone. The labor dissolves into design. The good thing, a ‘classless’ AI assistant, becomes the very thing to keep class relations real albeit more opaque than ever.

Apple users are promised the pleasures of feeling smart without discomfort. Apple Intelligence becomes the digital update of the invisible servant fantasy. Now, the servant has no face, voice, or wage. Guilt is designed out of the user experience. This is not to equate AI with slavery, but the structure of the fantasy—of frictionless, guilt-free labor—is historically resonant. The user’s convenience is predicated on erasing the laborer’s experience. Apple doesn’t show who trains its models or moderates content. It erases labor from the interface.

This is why Apple declares “AI for the rest of us.” The phrase promises accessibility but demands entry into a costly ecosystem. It flattens class, presenting all Apple users as equal participants in a tech utopia. The deeper lie is that anyone can be a master now—because the servant has no face, cost, or politics. Just a shimmer of “Liquid Glass.”

Apple’s AI ideology eliminates class and race from the visual field, not the material one. The reality of AI’s production—content moderation, data labeling, extractive economics—is simply not shown. Users are seduced into a post-labor fantasy: AI as magic, intelligence without infrastructure, assistance without responsibility.

This is the final twist of cruel optimism: the “good life” promised by Apple Intelligence disavows the conditions that make such a life unattainable for most. Apple doesn’t erase class conflict—it stylizes its absence.

Conclusion: Classless AI and the Politics of the “Good Life”

Across WWDC24 and WWDC25, Apple presents “Apple Intelligence” as seamless, ambient help for everyone. But this promise remains an illusion. By making intelligence invisible, Apple sells a fantasy of classless convenience, of labor without laborers.

The real “rest of us”—those without access to the latest Apple hardware—are excluded. The rhetoric of inclusion becomes a tool of erasure. Lauren Berlant’s cruel optimism captures the contradiction: a good life that denies the realities making it impossible.

Apple’s shift from Siri to ambient AI reflects this logic. Siri was someone; Apple Intelligence is no one. This transition severs the user from AI’s labor and politics, allowing them to feel empowered without responsibility.

Apple Intelligence doesn’t democratize AI—it aestheticizes inequality. It doesn’t eliminate class—it hides it behind glass. It doesn’t remove labor—it asks us to forget it ever existed.

References

[1] Apple, Reg. 2024. WWDC 2024 — June 10 | Apple. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RXeOiIDNNek.

[2] Jameson, Fredric. 2021. Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822378419, p. 9.

[3] Marques Brownlee, Reg. 2025. WWDC 2025 Impressions: Liquid Glass! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1E3tv_3D95g.

[4] Apple, Reg. 2025. WWDC 2025 — June 9 | Apple. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0_DjDdfqtUE.

[5] Liquid Glass bears another paradox: it gestures toward transparency—but its implications are more than aesthetic. As the YouTube channel Design Lovers observes, we’ve reached “the end of the era of curation” and entered “the era of the canvas,” where users gain more visual autonomy than ever before. Apple loosens its grip on how devices look—inviting play, personalization, and creative agency. Yet this surface-level freedom coincides with a deeper consolidation of control: Apple Intelligence, now seamlessly embedded, quietly assumes responsibility for increasingly consequential decisions. As Design Lovers aptly note, “design is a system for managing attention.” While users gain aesthetic agency, they cede epistemic agency—trading critical awareness for customization, and oversight for elegance. What appears transparent is, in fact, a distraction.

Source: Design Lovers, Reg. 2025. Apple Design: The Reflection That Ended an Era (iOS 26 design review).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DIOtkouGh90.

[6] Berlant, Lauren. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822394716.