Da Chven Vitsekvet, Regie & Drehbuch: Levan Akin, Schweden/Georgien/Frankreich 2019

Reviews/Kritiken by Sandro Chkhetiani, Emilio Noffke Manzano, Selina Teichmann & von Denise Wiedemann

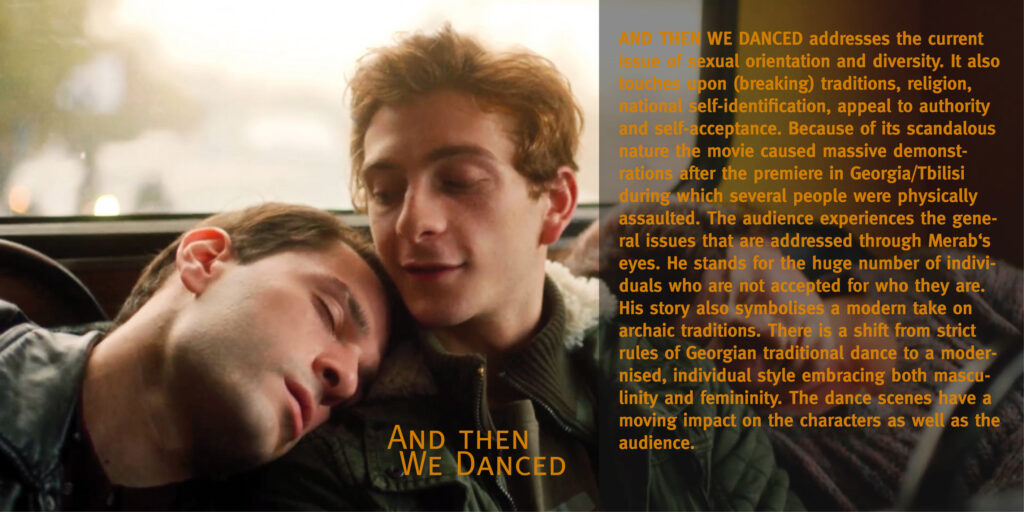

“Oh, Caucasus, the land of stern faces, strict rules and ancient customs! ” Or: How the most open-minded place in the region could not overcome a story about gay love.

by Sandro Chkhetiani

Homosexuality in Caucasus has always been a taboo, to even mention the existence of sexual minorities is labelled as propaganda in the best case or punished physically in the worst. Georgia, being a more tolerant place in many terms than its neighbours, also has a history of issues with the LGBTQ movement. The fact that the director, Levan Akin, shot a film about gay dancers was met with the expected outrage and attacks from the local majority. Taking into consideration the sensitivity of same-sex relationship topics in the region, one might assume that the rejection of the protagonists by society and their following survival would be the core problem of the film, but as it turns out, the director decided to show a genuine love story, primarily focusing on the romance, with the whole toxicity of society as a still important, but a more background element. Granted that AND THEN WE DANCED is sometimes repetitive in some of its ideas, it is also ultimately a necessary story that was depicted perhaps as best as it could be under the circumstances.

The film has every necessary aspect of a coming-of-age story: there is a main character, who discovers a new side of his personality and tries to explore his nature as clumsily and melodramatically as possible by smelling his crushes T-shirt or melancholically lying in bed with a man-who-was-cruelly-betrayed-by-the-whole-world-look on his face; he walks a long path filled with self-doubt and conflicts, which eventually leads him to mature. But as the movie progresses its melodramatic nature starts to feel even more forced. The director is either content with a form(ula) and its limited ways of showing the main character’s heartbreak phase or he is simply unaware of the repetitiveness and the overlong nature of the final third of his movie.

Apart from its main theme, AND THEN WE DANCED tries to highlight other significant topics of today’s Georgia: poverty, criminal activities – in which the main character’s brother ends up – and provinciality. These problems are depicted as a follow-up of each other, but the overall picture looks somehow overbaked, either because there are too many narrative strands crammed into a 113-minute film or because of an inability to connect all the above-mentioned issues more masterfully, which is a more likely reason.

Music is another important part of the film, thematically divided into modern and traditional parts. Apart from making the movie look more dynamic, it is also clear that music had a strong influence on the director’s vision even before he began the shooting process, as sometimes the perfect (rhythmic) synchronization between images and music gives it an aesthetic look usually associated with music videos. That being said, just like with melodramatisation, there also exists an over-saturation with soundtrack.

Levan Akin’s film staggers an awkward dance, which is probably justified in some way with its protagonist being young and unexperienced, yet the fact that most of the time the whole modern spirit of the film looks weak compared to the thousand-year-old iron laws of the region should not necessarily be understood in a pessimistic way. As it was stated in Tarkovsky’s Stalker: “When a man is just born, he is weak and flexible. When he dies, he is hard and insensitive. When a tree is growing, it’s tender and pliant. But when it’s dry and hard, it dies. Hardness and strength are death’s companions. Pliancy and weakness are expressions of the freshness of being. Because what has hardened will never win.”

Overall, AND THEN WE DANCED has its own light scented charm, but it follows a well-trodden path and is not ground-breaking in terms of genre conventions, bringing to the table a whole bag of melodramatic clichés. It is also not helping a movie, when the director decides to overuse his/her stylistic choices and decisions over and over again, which only devaluates the advantages of those choices. If asked about its impact in political/cultural terms, one can say that although it may not break the grip of Georgian conservatism nor change the mind of the mob, that tried its best to ruin the premiere of the film, AND THEN WE DANCED is one of those necessary first punches in the wall, that may look insignificant in the beginning, but are crucial in order to lead to a change in perception of a sensitive topic. The inevitability of this kind of art (and this film in this particular case) is written down in the very essence of the concept we call progress: one cannot keep going forward forever in ragged boots, at some point a nation can no longer keep a lid on its fears and insecurities but needs to deal with them. Maybe one day the critics, who are so afraid to lose their identity, will understand that they messed up with the notion of when they should fight and when they should dance.

Young Fire, Old Pride

by Emilio Noffke Manzano

One is to look back whilst moving forward, keep in step yet innovate – they demand hardness as shins break on wooden floors.

History and time seep through Levan Akin’s sophomore picture AND THEN WE DANCED (2019), a film about dance, love and tradition, perhaps in opposite order. In a time when the old is increasingly being labelled as outdated and formerly secure identities continuously lose their grounding, the public reaction to this film in its home country, Georgia, is symptomatic of the fear turned violence from those, who feel the world is leaving them behind. In advance of the premiere, multiple far-right and conservative groups proclaimed their intentions to stop the three national screenings, even going as far as saying they were prepared to take on police forces. They created a corridor of shame for audience members to walk through before entering the cinemas, burned pride flags and led nationalist and homophobic chants. But despite all this, they were not to succeed. All three screenings were sold out within minutes and the film is now being distributed in many countries for many more people to see.

Deep stillness: neither sounds nor cries—

Ilia Chavchavadze, Georgian poet, Elegy, 1859

Like parent to child, my Country told me little.

From time to time I heard an anguished sigh,

Sobs while a Georgian man slept and dreamt.

Merab (Levan Gelbakhiani), a young man in Georgia who has been training from a young age to become a professional traditional dancer, finds himself at odds with his surroundings as he pursues an exploration of his sexuality after a new member joins his dancing troupe (Bachi Valishvili). The film takes the audience from this starting point through the various steps and possible missteps of navigating non-heterosexual desire in a deeply traditional country, all the way to Merab’s final dance of empowerment. While this is not a traditional dance film per se – there are neither dance offs nor complete performances – dance is still integral to this film. It reflects values and tradition, values Merab aspires to, despite being told multiple times he was ‘too soft’ for traditional Georgian dance. This is one way history is trying to get hold of him, another is through his absent father, a former dancer himself, who discourages him to pursue this career altogether. Dangling in between multiple points of discouragement, Merab lacks the clarity to find his own path, illustrated by the film through handheld camera and a quick disjointed editing style. Over the course of the narrative, as Merab gives into his romantic desires, the editing becomes steadier, the shots become longer, Merab finds his solid ground. One must only compare the introductory and the closing dance sequence – the former full of jump cuts and quick, sudden pans, the latter fluid and elegant in its movement.

As his sexuality is being involuntarily disclosed to his dancing group, this offers the film the possibility to present the audience with different reactions by his peers, ranging from outright instant marginalisation to initial shock leading to loving encouragement. This beautifully culminates in perhaps the greatest shot of the film. While most of the film is almost exclusively centred around Merab – with many close-ups focused on him or the camera following closely behind him as he moves – for maybe the only time in the film, the camera breaks loose during a wedding celebration and freely roams the party in a long dolly shot, being witness to a sequence of images, which equate to the most sobering love letter to the Georgian nation: a banquet of food, a group of men fighting, a dancing bride, and in the background, seen through a window, Merab’s female dancing partner chasing after him and mending former wounds — in other words, tradition, violence, beauty and kindness, all contained within one shot.

Furthermore is to mention how the film elegantly connects Merab’s sexuality, his dancing, and the ‘Georgian spirit’. Early on in the movie we are presented with the dancing troupe’s dance instructor, who boldly states that, ‘there was no sex in Georgian dance’ and ‘Georgian dance represented the Georgian spirit’. The film goes on to prove him wrong by the use of stark yellow light for the Tbilisi night streets, intimate dance scenes, as well as Merab’s and Irakli’s first sexual encounters. One should notice that all LGBTQ-friendly locations are colour coded differently, the bar burning red, the club blinding white. It is the streets of Georgia which are yellow, and remain yellow. Georgian dance can include sex, and all kinds of sexualities.

Wretched, black—be whoever you can;

Titsian Tabidze, Georgian poet, Self-portrait, 1916

Oh life, I hold the reins in my hands

To transform you, this hell, into heaven.

Just as Merab dons a traditional robe for his final dance, which stems from a time before the hailing of ultra-masculinity in Georgian dance and culture, the film reminds us of an alternative to the unbridled pursuit of strength and rigour. It reminds us that the Georgian spirit goes beyond insecure notions of ultrahard masculinity. Georgia is, in fact, older than hardness.

In closing, an appeal to emotionality and softness through the words of Paolo Iashvili:

Where the pyramids stand in silence,

Paolo Iashvili, Georgian poet, In The Pyramids, undated

when the sun is being married,

I shall lie down on the sun-coloured sand,

where the pyramids stand in silence,

I shall want you,

your eyes,

your arms,

your tenderness…

DANCING – MOVING BOTH BODY AND MIND

by Selina Teichmann

„This film is not a coming out story. It’s a story about owning your identity and owning yourself in a culture that doesn’t want to accept you. And also, it’s a film about not allowing anybody to tell you what tradition is.”

Levan Akin (director)

With this statement writer and director Levan Akin describes the general topic of self-acceptance addressed in his third movie AND THEN WE DANCED – a topic that has always been and will always be relevant.

The key inspiration that started his project was Tbilisi’s first Gay Pride Parade in 2013. Fifty kids were violently attacked by thousands of people who formed counter demonstrations. A similar closed-minded hatred against people questioning Georgia’s traditions and social norms regarding homosexuality is depicted in AND THEN WE DANCED. Embedded in this contextual setting the main character Merab finds himself in a very worrisome position. He is constantly troubled by the fact that his intense feelings towards co-dancer and friend Irakli are empowering and beautiful, yet unaccepted in Georgia. After Irakli reciprocates his feelings a smile appears on Merab’s face that reminds the audience of a beautiful rose finally flourishing after a long period of darkness. However, his euphoria fades as quickly as it arose when his colleagues talk about a dancer named Zaza who was thrown out because of his sexual orientation. This story represents the general disapproval towards sexual diversity that Merab has to face.

Levan Gelbhakiani who won the award for “Best actor” at the 25th Sarajevo Film Festival, excellently portrays Merab’s character development through his encounter with Irakli. He thereby sets an example for embracing one’s own identity despite being ultimately rejected by others. In one of the first scenes he gets told off for being too soft. The reason: There is no room for weakness in masculinity-based Georgian dance! Is this cultural opinion related to tradition? Or is it rather narrow-minded and outdated? Director Levan Akin believes it is the latter since masculinity can be conveyed in many different ways. He therefore allows Merab to find and embrace his own kind of masculinity and tradition. He encounters a rough journey during which he allows his body and mind to evolve.

Smelling the lover’s shirt, crying and wanting the first sexual experience to be special – some might even call Merab’s sensual behaviour weak or unmanly. In the beginning of the movie there is a clear imbalance between his characteristic actions in everyday life and how he constrains himself to dance. At the ensemble’s dance rehearsals he tries desperately to shake off his individuality by forcing an unnatural stiffness into his body. It is the shrinking distance between Irakli and himself that enables Merab to get to know and learn to appreciate his sensuality. After their first sexual encounter Merab’s body language starts to change. A scene in which this can be seen shows the two men alone in the evening when Merab starts to dance. He puts on a wig which almost seems like he is putting on a different side of his personality, that he has not shown during dance before. In his own rhythm he dances for Irakli, softly and freely. He steps forward, spins and moves his hip, not taking his eyes off Irakli. In this moment no one tells Merab what traditions or rules to follow. He is allowed to define that himself. Carrying this new sense of freedom inside him Merab returns to the dance ensemble, where he refuses to stop even though his dance instructor repeatedly tells him to. But he is unstoppable! Ignoring the judge’s limited mindset he finally expresses a formerly repressed side of himself through dance. What an extremely powerful and literally moving image!

Yes, AND THEN WE DANCEDmight be as predictable as some critics have stated. It undoubtedly addresses well-known topics like homosexuality in repressive times that have already been highlighted by previous movies such as CALL ME BY YOUR NAME(Luca Guadagnino, 2017). However the movie also opens minds to social and cultural changes, which makes it a valuable piece of art. Levan Gelbakhiani’s attitude can be taken as an example: Although he had initially rejected his role several times he eventually opened up to the task. He learned to embrace the idea of powerful changes like Merab does in AND THEN WE DANCED.

Guadagnino lässt grüßen… auf Georgisch

von Denise Wiedemann

AND THEN WE DANCED (2019) ist der Versuch des schwedisch-georgischen Regisseurs und Drehbuchautors Levan Akin uns einen besonderen Einblick in das heutige Georgien zu geben. Eine Welt, in der traditionelle Kultur und moderne Lebensweisen aufeinandertreffen und für Kontroversen sorgen. Klingt vielleicht nicht danach, aber erinnert von der Handlung her stark an Luca Guadagninos CALL ME BY YOUR NAME aus dem Jahre 2017. Nicht nur gleiche Themen, wie Homosexualität, Kunst und Selbstfindung kommen in beiden Filmen vor, sondern auch einzelne Handlungsstränge aus AND THEN WE DANCED erinnern an den oscarnominierten Vorgänger. So betritt und verlässt ein unbekannter Neuling die Geschichte zu Beginn und Ende des Films und sorgt somit dafür, dass ein aufstrebender Teenager anfängt, sich mit seiner Sexualität auseinanderzusetzen. Während aber CALL ME BY YOUR NAME in Italien der 1980er angesetzt ist und eher auf eine romantisierende Darstellung baut, spielt AND THEN WE DANCED im heutigen alltäglich und lebensnah inszenierten Georgien, wo Homosexualität zwar rechtlich legal, aber immer noch gesellschaftlich verpönt ist.

Das Land südlich des Großen Kaukasus ist stark von der orthodoxen Kirche und seinen traditionellen Werten geprägt, weshalb es vor allem die Jugendlichen sind, die oftmals zwischen Tradition und Moderne hin- und hergerissen sind. So auch Merab (Levan Gelbakhiani) – ein junger Tänzer, der durch seine liebevollen Bemühungen, für seine Familie zu sorgen, zu Beginn eher wie das erwachsene Familienoberhaupt wirkt. Innerlich hingegen ist er aber ein ganz normaler Jugendlicher, der mit Selbstzweifeln, Zukunftsängsten und der Suche nach sich selbst zu kämpfen hat. Eine zentrale Rolle in dieser Selbstfindungsphase spielt dabei der neue Tänzer Irakli (Bachi Valishvili), welcher für Merab vom Rivalen zum Freund und schließlich zum ersten Geliebten wird. Zu Beginn noch überzeugt von Kultur und Traditionen, wie sie für ihn im georgischen Tanz verkörpert werden, beginnt Merab mit der Zeit zu zweifeln, ob diese (Tanz-)Welt wirklich die richtige für ihn ist.

Reden ist Silber – Tanzen ist Gold

Anstatt Klavier zu spielen und Gedichte zu zitieren, tanzt sich Merab durch den Film und das mit solch einer Energie, dass er es schafft, mit seinen Bewegungen nicht nur die Leinwand, sondern den ganzen Raum für sich einzunehmen. Da verwundert es auch nicht, wenn man erfährt, dass hier der Tänzer zum Schauspieler wurde und nicht umgekehrt. Die Tanzeinlagen wirken wie eine Kombination aus irischem Stepptanz, klassischem Ballett und asiatischem Kampfsport. Bewegungen, die der Protagonist perfekt zum traditionellen georgischen Tanz vereint. Nicht nur mit seinen akkuraten und starken Tanzeinlagen, sondern auch mit seinen sehr subtilen aber klaren Gesichtsausdrücken gelingt es Levan Gelbakhiani, die*den* Zuschauer*in an seinen innerlichen Gefühlszuständen teilhaben zu lassen und das Publikum zu ergreifen. Und das beschränkt sich nicht nur auf den Tanz. Wo an Dialog gespart wurde, wird die Geschichte mit Bewegungen erzählt. Sei es die erste körperliche Annäherung von Merab und Irakli, der bittere Kampf um Anerkennung oder die emotionale Botschaft am Ende mit welcher Merab zeigt, dass er sich nicht nur von künstlerischen sondern ebenfalls von sozialen Traditionen und Regeln loslösen will.

Wo Bewegung und Ausdruck vorherrschen, sind Worte überflüssig. Dialoge werden bewusst zurückgehalten um lieber Blicke, Berührungen und Farben für sich sprechen zu lassen. In diesen Szenen funktioniert der Film am besten, denn die Informationen, die durch Dialoge transportiert werden, sind meist zu offensichtlich und machen gewisse Handlungen vorhersehbar. Dadurch kollidieren die zugespitzen Dialoge des Öfteren mit der eher alltagsnah dargestellten Lebenswelt. Obwohl Levan Akin sich bereits an mehreren Drehbüchern früherer Filme textlich ausprobieren konnte, ist anzunehmen, dass er bei AND THEN WE DANCED kein Risiko eingehen wollte. Er versucht mit teils recht simplen Dialogen sein Anliegen und die Botschaft des Films eindeutig und unmissverständlich auf den Punkt zu bringen.

Weder schlechter noch besser als CALL ME BY YOUR NAME aber in vielerlei Hinsicht ähnlich, ist AND THEN WE DANCED ein gelungener Selbstfindungsfilm, der aus einer etwas anderen Perspektive erzählt und mindestens genauso berührt. Der Film ist zwar auf weite Strecken vorhersehbar und lässt somit an Spannungsaufbau missen, vermag es aber die*den* Zuschauer*in auf anderen Ebenen mitfühlen zu lassen und hinterlässt einen bleibenden Eindruck, der zum Nachdenken über gesellschaftliche Konventionen anregt.