Here’s why you need eye patches, gauzes, surgical face masks, and gas masks to participate in a protest safely in Hong Kong

by André Ho

How do the ordinary citizens of Hong Kong end up going out to the street to protest wearing eye patches, gas masks and face masks? Let’s have a little look back at the past. The transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong in 1997 officially ended the 156 years of British administration for the colony Hong Kong and the region became a special administrative region under China. Beijing has offered Hong Kong “one country, two systems”, which allows a status of autonomy. It has promised a universal suffrage to give the right to elect the government leader and the members of the legislative council. More than twenty years has passed since the handover, Beijing is still unable to fulfill the promise. The first series of protest broke out in September 2014 and the protests ended four months after without achieving any political concessions, but it triggered activists to take initiatives for fighting for the right to democracy and free vote. In 2019, the government of Hong Kong, led by the Chief Executive Carrie Lam, introduced the Fugitive Offenders amendment bill, which would have allowed the extradition of criminal fugitives who are wanted in territories, with which Hong Kong does not currently have extradition agreements, including mainland China. Due to arbitrary enforcement of local law in mainland China, this led to concerns that Hong Kong citizens and visitors are subject to the jurisdiction and legal system of mainland China. Demonstrations broke out after June 9th, and the police has been deploying tear gas, bean bags rounds and rubber bullets. The protest is still ongoing today and the police force were heavily accused of using excessive, disproportional force while omitting international safety guidelines and internal protocols, which causes major body injuries to the protesters.

Protest Art

The 2019 protest is generally known to have no single leader, nor has anyone or any political group claimed the leadership over the movement. Generally, the protesters identify themselves as either the peaceful, non-violent, moderate group or the radical group of fighters. Protesters who identify themselves as “fighters” are the ones who go out to the street, participate in the protest physically, and confront the police in the front line. On the other hand, the moderate group adopts a totally different strategy: they organize mass rallies and flash mobs, form human chains around schools, boycott pro-Beijing shops, and publicize their movement on different media platforms. One special trait about the Hong Kong protesters is that, there is a “publicity group” among them, who uses artwork, painting, and performance to spread the awareness about the movement and the event that have occurred in the city. Due to injuries caused by the alleged police misconduct, many of the artworks depict directly and indirectly physical body injuries. Over the course of the protest, I have collected many artworks on various social network platforms. These artists are usually anonymous or they adopt pseudo-names in order to protect their identities and avoid prosecutions. The artworks can be generally divided into 3 categories: direct messages, illustrations, and satire.

A Direct Message

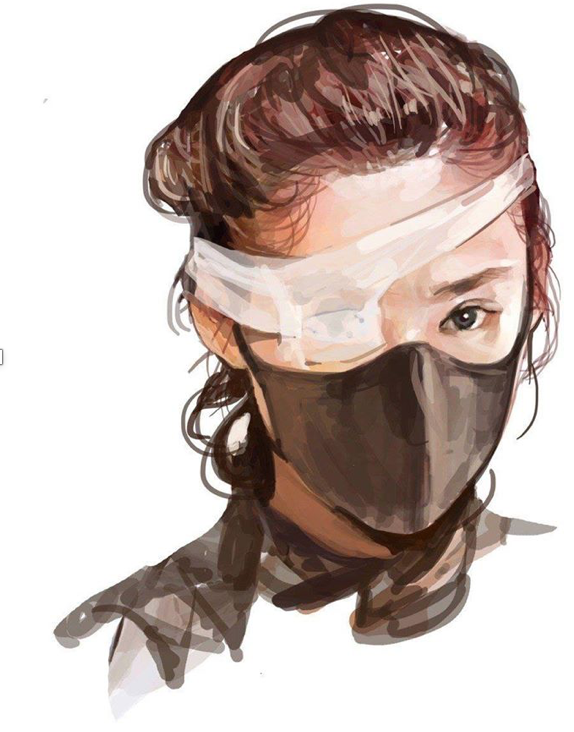

Pictures or posters that fall into the “direct message” category are straightforward and they are usually photos of the victims or from the scenes. Sometimes they are accompanied by short paragraphs of text describing the situation. One example is the photo of the volunteer medic whose right eye was shot by the police on August 11th,. Her real name and identity is not revealed by the media and she is commonly known as “the girl with an exploded eye” (original: 爆眼少女). Her cover photo on The New York Times (Fig. 1) covering her right eye made her internationally famous. During a video press release, she cited the Eye of Horus as a commentary to her injury: “I hope that my injured right eye, like the right eye of Horus in the mythology, has the power to keep the Hong Kong citizens from suffering and to defeat evil.”[1] She even has her own hashtag #爆眼少女 onvarious social media platforms. These posters or posts demonstrated that injured victims in the course of the protest can be depicted positively by the media and they serve to raise sympathy for the movement among the audience.

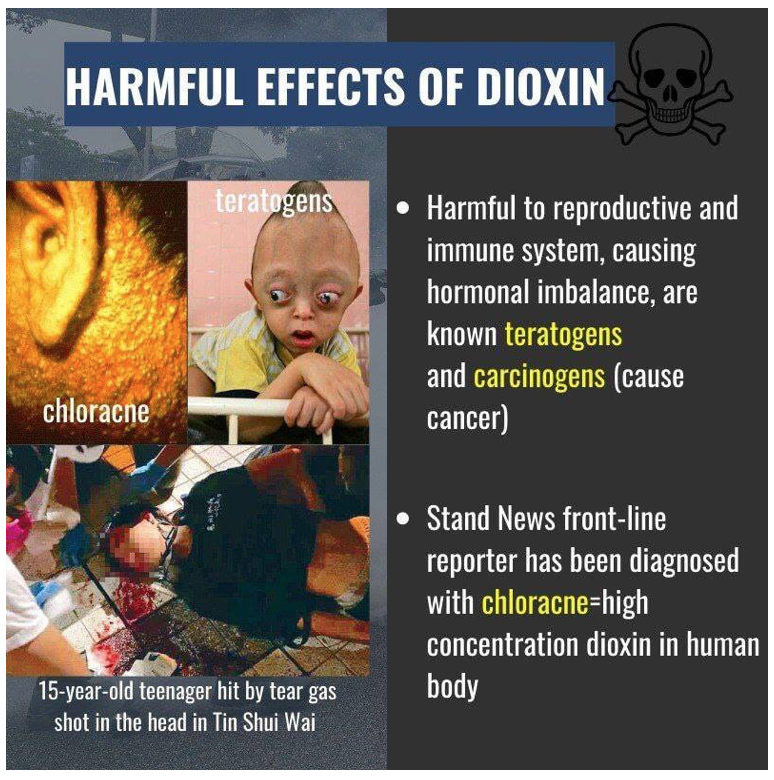

Sometimes the pictures do not have to contain photos of the actual victims nor directly from the scenes, and they can be from other sources. For example, there are pictures and posters circulated on the internet and on the street describing what the chemicals from tear gas would do to human body. Children with deformed body due to the usage of Agent Orange containing Dioxin in Vietnam after the war are commonly seen in the posters. Firstly, they serve an educational purpose, as the general public does not know what exactly the Chinese-made tear gas are made of, nor has the police force disclosed the information. Secondly, the grotesque images of deformed bodies aim to increase awareness among the general public in order to counter the excessive usage of tear gas by the police force.

Effluent Citizenship

If we look closely at the situation of the protesters in Hong Kong, they are pretty much politically, physically, environmentally, and economically disabled. Their right to free vote is taken away by the administration, thus rendering them to become politically disarticulated. Due to the excessive use of force by the police, they suffer physical injuries and the environment is endangered by harmful chemical substances. They often have to wear face masks or gas masks when they go out, because the police would deploy pepper spray and tear gas without warning. In Hong Kong, many shops and restaurants are owned by big enterprises, which are Beijing supporters or have Chinese backgrounds, due to the fact that tourists from mainland China are a vital source of income for local businesses. A deterioration of the sociopolitical situation and failure of addressing the issue of insufficient housing supply and high income inequality could further weaken the economic activity and negatively affect the city’s competitiveness in the long term.[2] Using Toby Miller’s Effluent Citizenship model, we can relate the Hong Kong protesters to the masked activists who protest against poor labour conditions in the electronic recycling industries. The ragpickers, as described by Miller, are also politically, physically, environmentally, and economically disabled.[3] Usually the protesters in Hong Kong would remain anonymous, in order to protect their employment, friends, and relatives. They offer to express their demands to change the malfunctioning political structure and to raise public awareness. They represent the effluent citizenship and the price of democracy is paid by the effluent citizen.

Illustrations

The second category is the “illustration”, which composes of paintings, photographs and artworks illustrating body injuries, like victims of the alleged police misconduct. The most common figure is the previously mentioned female volunteer medic, who eventually lost her right eye.

Illustrated subjects are commonly seen wearing an eye patch and a black face mask. The eye patch symbolizes body injury and the face mask serves to protect the identity of the individual. The protesters in Hong Kong adopted black bloc tactics by wearing black clothing, helmets, masks, scarves, sunglasses, or any other face-concealing items. Illustrations and artistic posters depicting injured victims appear on the streets and on Lennon Walls in various districts in Hong Kong. Illustrations are not limited to paintings, photographs, and posters; protesters use their own bodies to depict injuries. For examples, some protesters choose to wear eye patches, although they are not physically injured.

The Body as Battlefield

In the case of the protesters wearing eye patches and face masks, the practices are involved in the physical expression of an identity. They can be understood as casualties of the need, and responsibilities of the individual to create and maintain a distinctive “self-identity”.[4] The eye patch symbolizes a body that represents the turmoil of the time. The act of covering one’s right eye has also become one of the symbolic gestures of the movement. The face mask does not only eliminate the individual identity, but it also create a common, distinctive image of a “self-identity” of the Hong Kong protesters, thus bonding the members together symbolically. Since the movement lacks a leader nor a leading organization, the protesters would need a mean to form a bond or a connection to the other members. This can be observed after the Chief Executive Carrie Lam used the Emergency Regulations Ordinance from colonial-era to declare an emergency law on October 4th, which prohibits any form of face-covering activities in public. People wearing face masks in public without a valid reason could be fined, searched, or taken into custody. The government’s action sparkled heavy criticisms from the protesters. One month later, the High Court ruled that the anti-mask law is unconstitutional. The decision of the High Court proved that the face masks would be crucial, especially after the outbreak of the coronavirus. The protesters now wear surgical face masks not only to maintain their their common image of the “self-identity”, but to protect them from contracting the coronavirus through daily face to face contacts as well.

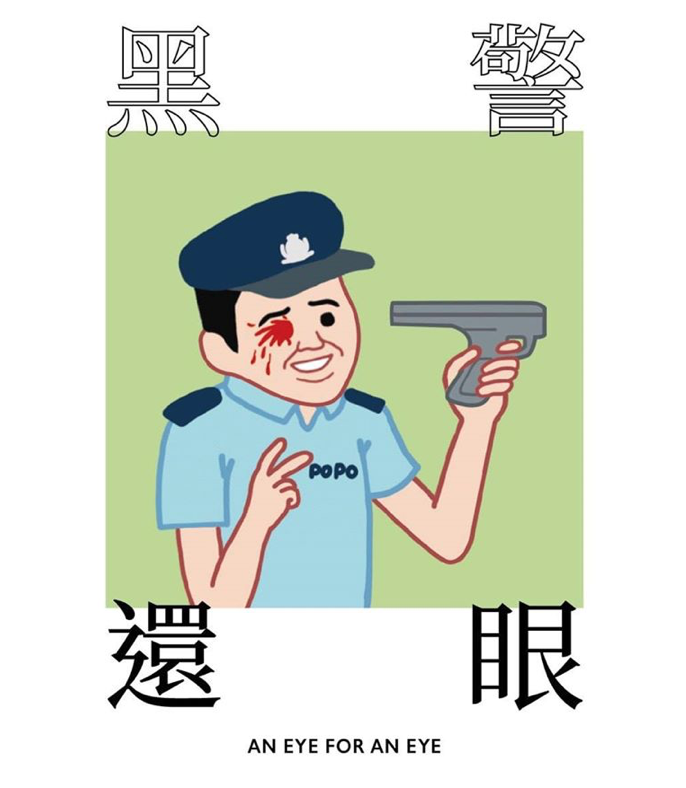

Satire

The last category is satire, which aims to shame or ridicule the government, the police force, pro-Beijing politicians, and officials in a humorous manner. Some of the artworks are derivatives of existing artworks. Images depicting body injuries that fall into this categories make mostly negative impressions. Many of the satire artworks targeted the police force because of their reported misconducting behaviour and disclosure of vague and ambiguous information during their press conferences.

Some of the artworks contain references to various figures from the popular culture. For example, a toy artist used the alien figure from Steven Spielberg’s E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial to depict a policeman’s wife giving birth to a baby affected by teratogen caused by tear gas. The purpose is to utilize the images of body injuries or sickness to give new interpretations to the existing artworks and figures from the popular culture. The image of disabled body in this category is used differently than the previous categories.

So, how should we interpret them?

The protesters in Hong Kong have created a variety of artworks showing disabled bodies to raise awareness and demonstrate their solidarity and identity. These artworks were generally produced to express dissatisfaction with the government, boost morale, and to form connections to each other. Protesters have often taken inspiration from the popular culture and the images of disabled bodies have also become the source of their creativity. By creating these artworks, they participate in the protest in an unconventional way. They no longer have to physically partake in a march, in which they moved their protest digitally to social media platforms. Most importantly, they don’t want to become a casualty while enjoying their freedom of speech, which has not yet be taken away from them.

[1] The Standnews: »【民間記者會】爆眼少女錄影發言 感謝市民挺身而出 望再無示威者受傷被捕«. The Standnews. URL, last access: 7.2.2020.

[2] Beech, Hannah: »Yellow or Blue? In Hong Kong, Businesses Choose Political Sides«. The New York Times. <https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/19/world/asia/hong-kong-protests-yellow-blue.html >, last access: 7.2.2020.

[3] Miller, Toby: »The Price of the Popular Media Is Paid by the Effluent Citizen«. In: Disability Media Studies.New York: Univ. Press 2017, pp. 295–210.

[4] Simonsen, Kirsten: »Editorial: The Body as Battlefield«. In: Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. April 2000, Vol.25(1), pp. 7.