by Oona | 15th Feb 2022 | Issue The Caring Media

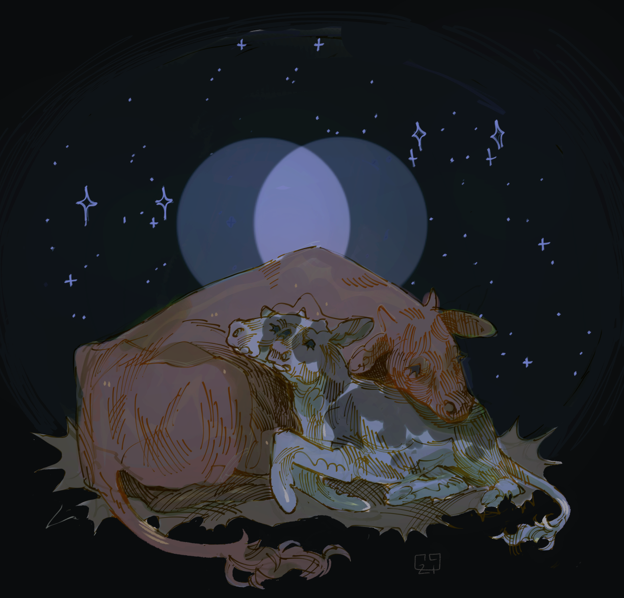

Laura Gilpin’s poem “The Two-Headed Calf” (1976) has seen a surge in popularity over the last few years on social media. It inspired people to make and share art (see Fig. 1), music, and memes; they got tattoos and endlessly discussed the feeling they got while reading it. I wasn’t spared. The first time I read the verses, they struck something within me. I won’t keep these lines from you any longer. So here it goes:

“Tomorrow when the farm boys find this / freak of nature, they will wrap his body / in newspaper and carry him to the museum. / But tonight he is alive and in the north / field with his mother. It is a perfect / summer evening: the moon rising over / the orchard, the wind in the grass. And / as he stares into the sky, there are / twice as many stars as usual.” [1]

Laura Gilpin

Did you feel it too? It causes a kind of lovely pain that I couldn’t put my finger on at first. The poem strikes a certain balance. It conveys the significance of a loving and caring moment despite the transience of life; all of that is positioned in front of the backdrop of the vast universe. The wind, the grass, and the care and love of a parent–these things are significant. There exists something between birth and death, though it may be fleeting. We are more than just matter that is dying from the get-go. Our experiences are meaningful, no matter how small and fleeting.

Mechanics of Care

The indie adventure game Night in The Woods (2017) hits a lot of the same notes as Gilpin’s poem about the starry-eyed calf. We play an anthropomorphised cat named Mae, a 20-year-old college dropout, as she moves back into her parent’s house in a small, former mining town located somewhere in the rust belt. Throughout the game, we see Mae trying to deal with her unstable mental health as she seeks to rekindle her relationships with the residents of Possum Springs and tries to rebuild her passion for her old hobbies. Several mini-games mostly centre on the various shenanigans she gets up to with her friends, while the majority of the game is spent exploring the town and talking to its citizens. Kevin Veale describes in his article “Responsibility and affective materiality in Undertale and Night in the Woods” how the medium of the digital game is especially potent in encouraging empathetic engagement with fictional worlds. [2] Regarding Night in the Woods’ gameplay he writes:

“NITW does not subvert the fundamental mechanics of gameplay. Instead, it uses the very constrained context of its protagonist to tell a story that uses the player’s perception of responsibility to explore themes of rural marginalisation under capitalism, mental illness, horror, desperation and hope.” [2]

Kevin Veale

Each day inside the game brings new dialogue options and opportunities to connect to a variety of characters. Much like the two-headed calf, Mae’s hometown Possum Springs is dying from the get-go. The former mining town is a shadow of what it once was. Old murals depicting miners and family stories of union uprising let the players catch glimpses the past. (See Fig. 3) Possum Spring’s community has a solid working-class background but struggles to keep things running now. Closed-down businesses, run-down apartment buildings, and hopeless faces mark the landscape. Especially the town’s young people are stuck in low-paying, ‘low-skill’ jobs as they work hard to escape the town for good one day. Feeling responsible for Mae’s actions and caring for her friends, family and surroundings are what drives Night in the Woods story and gameplay ultimately. Aside from Mae, the players spend the most time getting to know Mae’s friends Gregg, Angus, and Bea. In turn, we learn to understand and empathise with their struggles. And, as Veale writes, “we become invested in marginalised characters and a social context that are very rarely represented in media, particularly in games.“ [2]

Gregg and Angus are, according to Gregg, the only openly queer couple in Possum Springs. Mae’s homecoming stirs trouble in their relationship as Gregg is starting to neglect his responsibilities in favour of getting up to mischief with his returned best friend. Angus becomes frustrated with Mae and Gregg for being careless. Both he and Gregg work seven days a week in hopes of saving enough money to make it out of town one day. Although they ultimately work things through, the whole situation demonstrates how Mae (as well as the players) might be blind to her privileges. Mae lives on “the good side of town” and, although her parents are not affluent, they are still able to support their daughter financially, as well as emotionally. Mae’s self-centric tendencies become especially apparent in her relationship with Bea. Although they were close in childhood, Mae never noticed that Bea’s mom died during their school years, which resulted in Bea taking over her family’s business at a young age. She never got the chance to receive a higher education, even though she was top of her class. The fact that Mae seemingly flunked out of college on a whim makes Bea resent her initially. As the two of them spend more time together and lend each other support, their relationship slowly starts to heal.

A Freak of Nature

Much like the two-headed calf, Mae is considered to be a “freak” by the townspeople and even herself at times. (See. Fig. 3) She suffers from symptoms linked to depression, anxiety, and dissociative disorders. The players often have no control over Mae’s reckless and self-destructing behaviour. Many of her frustrations and aggravations can easily be seen as the reaction to her current situation in life and the lack of perspective Possum Springs offers. For example, she goes out and smashes light bulbs with her friends because there is simply nothing better to do. Still, her feelings of self-loathing and hopelessness go deeper than social circumstance alone. Throughout the game, it becomes more and more apparent that she battles with a lack of control over her actions and emotions. Or, as Veale writes: “Mae Borowski is a rare character within popular culture and particularly within video games, in that she is a young woman who is allowed to be a human disaster.” [2]

Her issues with mental health seem to be rooted in her genetics. Her mom is continually plagued by sudden mood swings, while her dad has a past with alcohol addiction and violence. It is suggested that her father’s illness directly resulted from his abrupt unemployment due to the economic decline of Possum Springs. While neither of her parent’s struggles is explored in-depth they nevertheless situate Mae’s neurodivergence as a result of bodily and social circumstances.

Mae’s biggest source of distress and the reason she dropped out of college is her tendency to disassociate. A violent incident caused by one especially bad episode during a school softball game left her and the town terrified. In a conversation with Greg or Bea (depending on who the player chooses to spend time with) Mae describes how she started to disassociate initially: “Something broke in my head. My life.” Her relation to the world and everything she cared about crumbled. “It was all just stuff. Stuff in the universe,” she explains. This loss of connection to the world made her feel isolated and alone. Bea/Gregg offers to support Mae. Gregg insists: “You’re gonna be okay. […] I’ll be here all night.” While Bea reassures her: “What you’re going through, it exists.” When, towards the end of the game, Mae tries to face a dangerous situation alone Angus, Gregg, and Bea insist on coming with her. Gregg says: “Even if this was all somehow in your head. Which it isn’t. I would still back you. To the actual God’s honest end.”

Just Shapes

While the days in Night in the Woods are spent building relationships and smashing things, the nights centre on Mae’s dreams. The players learn a lot about Mae’s past, her inner feelings of rage, and nihilistic despair through these dream sequences. In her last nightmare, she comes across a giant cat, dubbed the Sky Cat, among a starlit desert. When Mae asks the Being if it is God it denies: “I am not this God. And this God is nowhere.” As Mae inquires further the being continues:

“There is a hole at the center of everything, and it is always growing. Between the stars I am seeing it. It is coming, and you are not escaping, and the universe is forgetting you, and the universe is being forgotten, and there is nothing to remember it, not even the things beyond. And now there is only the hole… You are atoms, and your atoms are not caring if you are existing.”

The Sky Cat in “Night in the Woods”

The Sky Cat mirrors Mae’s struggles with disassociation. After all, if everything is just “shapes” does anything matter at all? The philosopher Guy Kahane discusses a similar concept in his paper “Our Cosmic Insignificance”. The notion that life on earth–especially human life–is just a blip compared to the history of the universe, may infer existential anxiety or even nihilistic resignation in people. There was an eternity before us and an eternity after us–why should our short existence matter? Or as Kahan puts it: “The universe is immense, and we are so very tiny.” [3]

The Hole In The Centre Of Everything

The nihilistic despair that many people experience while pondering our cosmic insignificance may often be a result of rejecting the notion that a God can exist. Despair as the consequence of a loss of faith is a common motif in media that deals with coming of age that is also present in Night in the Woods. The game conveys this directly through conversations about religion and faith. After her dream with the Sky Cat, Mae seeks reassurance from the town’s Pastor, who tries to reinstall a sense of community and compassion into Possum Springs. Despite her best efforts the city council refuses to house the homeless and care for strangers. Spending time with Angus also reveals that he has suffered abuse in his childhood at the hands of his parents. Despite his insistent prayers, there was no divine intervention through a compassionate higher power. Pastor K. waivers in her faith from time to time, while Angus loses it completely. The “hole in the center of everything” that the Sky Cat referred to could refer to the nihilistic emptiness left in the place where the faith in God once was.

There is also a literal hole in the centre of Possum Springs. The abandoned shafts from the former mining days reach deep under the town’s surface. In the finale of the game, the four friends face a cult of townspeople that believe sacrificing ‘hopeless’ individuals to the mineshaft will restore the town to its former glory. This as well could stand for a loss of purpose. The hole inside Possum Springs is both literal and metaphorical. The mining industry gave the Possum Spring’s community an identity built on being hard-working and resilient. The economic decline of the town left a void where there once was a sense of direction.

Tracking Constellations through Cosmic Insignificance

Longest Night (a game that appeared supplementary to Night in the Woods) as well as a reoccurring mini-game in the main story, let players track constellations through the starry sky. The found constellations reveal the world’s most important spiritual and mythical stories. The stars themselves might not have meaning, but the constellations do. Or, as Angus puts it:

“We’re good at drawing lines through the spaces between stars like we’re pattern-finders, and we’ll find patterns and we like really put our hearts and minds into it and even if we don’t mean to. So I believe in a universe that doesn’t care and people who do.”

Angus in “Night in the Woods”

So, “[w]hy should we be insignificant just because the universe is vast?” [3] In the end, according to Kahan, the size and longevity of our existence don’t matter in the question of whether we are significant. Although there are several different approaches to answer this question, I think that Night in the Woods’ tagline does a pretty good job: “At the end of everything, hold onto anything”. Be it the wind, the grass, or the care and love of a friend.

References and Annotations

[1] Laura Gilpin. “THE TWO-HEADED CALF.” The Transatlantic Review, no. 57, 1976, p. 125.

[2] Kevin Veale. “‘If Anyone’s Going to Ruin Your Night, It Should Be You’: Responsibility and Affective Materiality in Undertale and Night in the Woods.” Convergence (London, England), 2021.

[3] Guy Kahane. “Our Cosmic Insignificance.” Noûs (Bloomington, Indiana), vol. 48, no. 4, 2014, pp. 745–772.